Introduction

Bill Kirchner has been mentioned fairly regularly in my jazz pieces ever since he and I first became friends in August of 2014. This began and has continued mostly in cyberspace as Bill left a couple of comments on my site then followed these up by emailing me personally. He introduced himself, saying he knew of my work with the Boss Brass and commenting that he enjoyed my blogs and admired my writing, which, coming from such an accomplished writer, took me aback somewhat. In typical mensch-like fashion he offered to do anything he could to help with my writing, including spreading the word about it, which he has certainly made good on. As our correspondence continued and we exchanged a lot of information, observations and stories, Bill crept into my head more than a little. He has an immense knowledge of jazz and a phenomenal memory, so I began learning a lot from him straight away, hence the frequent mentions in posts. Indeed, I could have a separate blog just devoted to our many exchanges, perhaps called “Conversations with Bill Kirchner” or something. We’ve gotten into all kinds of music stuff small and large and he has certainly given me many ideas about jazz subjects to write about, more than I can keep up with in fact. I’ve got to learn to type faster.

I’ve been intending to write a piece on him for a long while now, in fact I must confess I have begun to do so many times and either stalled or aborted altogether, chucking out a few thousand words in the process. Beyond time constraints, various distractions and illnesses, the problems have been twofold. For one, being something of a retro-maniac, I’m much more comfortable writing about the distant past and jazz people who I don’t know, or who are dead. It’s just the way I’m wired and writing about someone I know and admire as much as Bill has proven daunting because I fear I won’t do the subject justice, won’t be up to scratch. I regard him as a friend and colleague, but he has also become one of my jazz heroes and, as I’ve discovered, writing about your heroes when they’re not at a safe remove can be a bitch. But the biggest problem in writing about Bill is that the extremely broad-ranging diversity of his accomplishments makes it hard to see the forest for the trees. More than once in print he has been described as a jazz renaissance man and in his case, it’s no idle exaggeration. The issue is not having too little to write about but rather too much, so how to begin?

To give just an overview, Bill is all of the following: primarily a soprano saxophonist now but for many years an experienced multi-reed doubler who also played E-flat sopranino, alto, tenor and baritone saxophones, clarinet and bass clarinet, flute, alto flute and piccolo; a widely-respected arranger/composer who has written charts for Dizzy Gillespie, Lee Konitz and many for the nonet he led for over twenty years; a jazz educator whose list of former students reads like a “Who’s Who” of jazz over the last 30 years. For good measure he is also a very accomplished jazz writer/historian and scholar, having written many published articles, liner notes and annotations, including the notes to the reissue Miles Davis and Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings for which he won a Grammy. He has also edited two major jazz books – the massive Oxford Companion to Jazz and A Miles Davis Reader, for my money one of the very best books on that much written-about musician. He’s been active as a producer on radio, with four hour-long NPR profiles on Bob Brookmeyer, Benny Carter, Artie Shaw, and Johnny Mandel; and as a host/producer of 131 episodes of WBGO’s Jazz From The Archives. He also has produced or co-produced many records and reissues, including the six-CD set Bill Evans: Turn Out The Stars, The Final Village Vanguard Recordings. It’s almost exhausting just to think about, but these are just the highlights. So, to borrow one of Ed Bickert’s better lines about an entirely different subject, writing about Bill Kirchner is a little like changing the fan belt on your car while the engine is still running – how do you get in? At any rate, this piece is long overdue and I’ve decided it’s time to get off the pot, so to speak.

***

Learning all this about Bill shortly after meeting him in cyberspace, I was left puzzling over two questions. One, how in the world could one man, no matter how multi-talented, find the time and energy to wear so many jazz hats and wear them so well? And two, why hadn’t I heard more of his music, or know more about it? I knew he played saxophone and did some arranging but mostly I knew of Bill through his liner notes, in particular the extensive ones he wrote for the Mosaic box set of the Verve recordings of Gerry Mulligan’s Concert Jazz Band. In fact, as I would come to find out, I’d read much more along these lines by Bill than I realized but hadn’t been paying close enough attention, as usual.

Not being familiar with his music could be put down to a number of things – jazz has become such a hugely crowded field that it’s impossible to be up on all of it, and not all the music recorded in New York makes it to Toronto, especially if released on smaller indie labels with limited distribution. But most of all, my listening and record-buying habits have mostly been firmly historical, a kinder and gentler way of saying I have a tendency to live in the past. While I like contemporary jazz, I prefer hearing it live; I’m much more apt to buy a record made in the fifties or sixties than one from the nineties.

As I was to find out, the answer to the paradoxical questions about Bill’s exceptional versatility and my unfamiliarity with his music has to do with the fact that there have been two Bill Kirchners, or more accurately his jazz career has come in two halves: the one before his illness-induced disability in 1993 – which involved much more playing and arranging – and the one afterward when he was forced to earn more of his living from writing, teaching and producing. He’s done so much not only because he could, but also because he’s had to. As Lester Young would have put it, necessity is a motherfucker. And in the best sense of that multi-purpose word, so is Bill Kirchner.

I’ll return to his fateful health issues in more detail later, but perhaps it’s best to begin at the beginning with an overview of his life and career.

He was born August 31, 1953, in Youngstown, Ohio, a once-busy steel town but now part of America’s rust belt. And, as Bill revealed, much to my surprise, a city with a considerable Mob presence in its prime: bloody hit-jobs and cars exploding in driveways were not uncommon. He caught the jazz bug at age five, mostly from watching shows like Peter Gunn on TV. The dissonant harmonies and jagged rhythms got to him, as did a vague sense that this music was hip in a forbidden, underground way. He took up the clarinet at age seven; indeed, one of the many things that distinguish him from most contemporary reed players has been his continued devotion to that now-maligned instrument. He added the saxophone – tenor at first – at age twelve and took up the flute while in high school. Another early inspiring moment came from hearing the Duke Ellington Orchestra play “Satin Doll” on the Ed Sullivan show one Sunday night when he was ten. “Satin Doll” has been overplayed to the point now where it’s almost a lounge joke but Bill has said that hearing it played by that saxophone section with Duke’s inimitable voicings was a life-altering experience.

Another key event came when the almost twelve-year-old Bill cajoled his parents into taking him to the Pittsburgh Jazz Festival, a star-studded three-day June weekend event directed by George Wein. It was held intermittently between 1964 and 1972, but the 1965 edition Bill attended was the most memorable, with a piano summit concert involving Mary Lou Williams, Ellington, Earl Hines, Billy Taylor, Willie “The Lion” Smith and Charles Bell being issued on record by RCA. The young Bill was fixed on hearing Ellington’s band which appeared on the Saturday night and he has written a wonderful retrospective account of the thrill of hearing them in person, also touching on the shock of hearing the John Coltrane Quartet precede Ellington on the same stage. Their music was way over his head and his parents and most everybody else there hated them, but there was nothing to do but sit through it in order to get to Duke.

Always a big reader, by the time he got to high school he was devouring everything about jazz he could get his hands on and haunting local record shops, drugstores and the like in search of bargain delete-bin jazz albums, all of which he still has. He took saxophone, clarinet and flute lessons from a man named Albert Caldrone who played principal clarinet in the Youngstown Symphony but also did some big band jobbing on alto saxophone and appreciated jazz. He benefited from a good high school music department with a big band and a hip director named Sam D’Angelo who liked jazz and recognized Bill’s keen interest. One of the trombonists in the stage band was Mark Dailey, who would go on to become well-known to Torontonians as a colourful news anchor on City TV. Bill was already interested in arranging and he wrote his first charts for the stage band with D’Angelo’s blessing. D’Angelo also lent Bill some good jazz records including one by the Rod Levitt Octet which would prove prophetic, as Levitt’s unique writing involving a three-man reed section using a lot of woodwind doubles would have a profound impact on Bill’s later arranging style. I didn’t discover Levitt’s records until quite recently through Bill, but he has to have been one of the very few teenagers to be aware of them. He also met some local musicians such as saxophonist Ralph Lalama – who would become a close musical associate for years – and his brother Dave, a fine pianist. Pianist Harold Danko, six years older than Bill, was also from Youngstown, but Bill wouldn’t meet him until 1973 in New York. Danko would become a close friend and one of Bill’s teachers in matters of harmony and some basic piano technique.

For someone who’s been so thoroughly immersed in the music in so many ways, Bill was somewhat reluctant to jump into the jazz life with both feet in the early going, perhaps lacking self-confidence and taking a have-something to-fall-back-on-just-in-case position. In 1971 he opted to go to college in New York because that’s where the music was happening, but his degree is in English literature, not music. He went to Manhattan College in the North Bronx neighbourhood of Riverdale, ironically a stone’s throw from where he now lives. But his jazz obsession was too strong to be abandoned. He began taking saxophone lessons with Lee Konitz – as he couldn’t afford the full hour at fifteen dollars he took eight-dollar half-hour lessons once every two weeks for two years. It was money well spent as Konitz completely turned him around as an aspiring improviser. Bill has described his playing at the time as a rudimentary Coltrane imitation, playing as many notes as possible with no real idea of what he was doing. Konitz stripped things down and got him into the essentials of playing melodically, of hearing and constructing real lines and thinking more compositionally, which would become a major thread in his playing.

As best he could on a skimpy budget, Bill also took advantage of hearing as much live jazz in Manhattan as possible – Konitz with La Monte Young, the Elvin Jones Quartet with Joe Farrell, Dave Liebman and Gene Perla, Chick Corea and Return to Forever, lots of Thad Jones and Mel Lewis on Mondays at the Vanguard, Sonny Rollins with Albert Dailey, Larry Ridley and David Lee, Mingus’s all-star big band at Philharmonic Hall with Konitz, Gerry Mulligan and Gene Ammons. To this day he’s adamant that the seventies were a much richer jazz period than is generally acknowledged and that anyone who says different just wasn’t paying attention.

After college, about to get married and needing money and a job, he decided to move to Washington, D.C. He’d taken and passed the Civil Service exam and took a job at the Department of Agriculture, which is a little hard to picture now. He wrote and edited articles there, but eventually he met the jazz critic/writer J.R. Taylor who worked at the Smithsonian Institute assisting critic and historian Martin Williams in running the Jazz and American Culture Program. In fairly short order Bill was working there, honing and applying his abilities as a jazz researcher, annotator, writer and historian while editing transcripts of oral history interviews. In the late-seventies he became assistant curator of the NEA Jazz Oral History Project, conducting lengthy interviews with Cozy Cole, Clarence Hutchenrider, Eddie Sauter between 1979 and 1982, Johnny Mandel in 1995, and Dave Liebman and Lee Konitz in 2011. The Smithsonian connection proved to be extremely valuable and in those Washington days he began to write articles on jazz for Down Beat, Radio Free Jazz (now Jazz Times), Jazz Magazine, and the Washington Post. The recognition he received as a jazz writer during this early period would prove invaluable later on.

At the same time, he took advantage of Washington’s jazz scene, much smaller and less pressure-packed than New York’s, but nevertheless vibrant and most importantly, openly welcoming. He met the pianist Marc Copland, who would become one of his closest musical associates right up to this day, and he began sitting in a lot at clubs such as Blues Alley, Harold’s Rogue and Jar, and One Step Down, finding himself accepted in the company of veteran local musicians such as Buck Hill, Marshall Hawkins and Nathen Page. He ran Saturday afternoon jam sessions at One Step Down which began bringing in players from New York on weekends.

Maybe the most important thing that happened to Bill during that period was meeting arranger Mike Crotty and hearing his music for the first time. A friend told Bill about a rehearsal band that played Sunday mornings at Catholic University. He went over one Sunday morning and as he walked in, he heard a big band playing an incredible chart of “Sittin’ On the Dock of the Bay” that sounded like Thad Jones – in that league, but it was by Crotty, who very few people knew of because he was a staff arranger for the Air Force jazz big band, the Airmen of Note. Crotty was an inspiration and became a huge influence on Bill, who considers him one of the truly great composer/arrangers despite an underdeveloped reputation caused by his out-of-the-way military position. Eventually Bill took a chair in the Sunday morning rehearsal band playing tenor, soprano, flute, alto flute, piccolo, and clarinet – he was already becoming an accomplished doubler and, as would become a common thread in his own writing, he was experiencing first-hand the exciting colour possibilities of woodwind doubles mixed with saxophones.

He began writing charts for the band, one of which landed him an NEA grant to study with Thad Jones. The only problem was by that time Jones had left to settle in Copenhagen. Bill asked his friend Sy Johnson about studying with him but Johnson politely declined, saying the right teacher for the job was Rayburn Wright, who ran the Jazz and Film Scoring Department at the Eastman School of Music. After hearing a tape of Bill’s work, Wright took him on and for about a year Bill flew to Rochester once a month for a lesson. It made him as an arranger. Bill feels strongly that Ray Wright at Eastman and Herb Pomeroy at Berklee were the two most important composing and arranging teachers in the history of jazz, teaching more important arrangers between them than anyone else. A decade later, Bill also had the opportunity to study with Bob Brookmeyer and Manny Albam in the BMI Jazz Composers Workshop.

So, while his stay in Washington didn’t exactly begin with jazz purposes in mind, it ended up being far more beneficial in that sense than could have been expected. Armed with more confidence and experience as both a player and arranger and having amassed some savings, he decided to move back to New York in July of 1980 and pursue a full-time jazz career. He credits his friends and fellow saxophonists Gregory Herbert and Pat LaBarbera for giving him the final ‘kick in the ass’ towards this commitment. He called everyone he knew, started hustling gigs and fairly quickly found himself working regularly. He formed his nonet in 1980 as an outlet for both his jazz playing and arranging, also staying busy with all-purpose gigging around the New York area as a sideman – clubs, weddings, concerts, some studio work where his doubling came in handy.

He was a frequent sub with the Mel Lewis Orchestra (now the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra), in fact he almost landed an alto chair with the band but it didn’t quite happen. He commented philosophically to me that he wasn’t quite the right fit for the band, nor it for him, so no regrets. Bill is a huge admirer of Thad Jones and of the VJO and knows more about both than anyone I’ve met. I’ve always been a fan too but he has filled me in on all sorts of personnel changes, different periods and bootleg recordings by the band I otherwise wouldn’t have heard. He probably should have written a book about the band but time didn’t permit.

After rehearsing for a few months, Bill’s nonet began to get some work at clubs such as Condon’s, Seventh Avenue South and the Jazz Forum, as well as doing festivals and college concerts. The idea was to have a band that combined the ensemble power and tonal range of a big band with the flexibility and improvisational freedom of a small group, striking a balance between written music and room for blowing. While there were some shifts in personnel it was mostly stable, the instrumentation being two trumpets, bass trombone, three saxophones with a lot of woodwind doubling on flutes, clarinet and bass clarinet, and a piano-bass-drums rhythm section. In terms of style and repertoire it was wide open, with both fresh treatments of standards and originals by Bill and other jazz players; some straight ahead things, some Brazilian music, some modal-based tunes, even some funk and a touch of ‘free’. It was firmly contemporary but had touches of tradition, something which has marked much of Bill’s work.

The band succeeded brilliantly in its musical goals both because of Bill’s very imaginative writing, full of colour and textural combinations rarely heard, and because of the execution of the first-rate musicians involved, both in terms of soloing and ensemble work. Fairly constant among these were Brian Lynch, who handled most of the trumpet solos, Douglas Purviance on bass trombone, Ralph Lalama on tenor, clarinet, flute and alto flute, with Marc Copland or Carlton Holmes playing piano, Mike Richmond or Chip Jackson playing bass and Ron Vincent the most frequent drummer. And of course Bill, playing soprano, alto, clarinet, flute, alto flute and piccolo. The third reed chair was held by three different players – early on Glenn Wilson playing baritone and flute, later Kenny Berger who added bass clarinet to that mix, and very interestingly, Michael Rabinowitz, who appears on the live double-CD Trance Dance, playing bassoon and bass clarinet. It’s the most effective use of the bassoon in a jazz context I’ve heard, audacious and uniquely colourful.

Above all it’s Bill’s writing concept that makes the nonet so invigorating and successful. It’s very orchestral with extremely varied combinations of instruments used in an organic and integrated way, it never devolves into being what he calls a ‘nine-piece quintet’ with an ensemble theme, a string of solos and a head out. There was plenty of room for blowing but the soloists were arrayed within an overall orchestral structure that never becomes formulaic. While he has been influenced by and admires many writers – Duke Ellington, Billy Strayhorn, Eddie Sauter, Mike Crotty, Bob Brookmeyer, Gary McFarland, Thad Jones, Gil Evans and Mike Abene, among others, Bill’s writing for the nonet was primarily influenced by Rod Levitt (particularly the multifaceted reed colours) and Herbie Hancock’s writing on The Prisoner, with its heavy use of bass trombone, alto flute and bass clarinet. Bill has said the nonet’s output – five albums and many, many appearances – is what he’s most proud of in his career. I’ll return with further commentary on some of their recordings in Part Two of this piece.

So things were going well for Bill, he was making a comfortable living and in 1991 he also began teaching regularly at The New School (advanced composing and arranging, jazz history and directing jazz ensembles). In 2002 he began teaching at New Jersey City University, which he abandoned in 2015 when the commute got to be a little much. He began teaching at The Manhattan School of Music in 2004, with an in-depth course on Duke Ellington and recently adding one on Miles Davis.

In 1993, as he was approaching 40, he began to notice some small mobility issues – stiffness, fatigue, sometimes his fingers wouldn’t quite do what they were supposed to. He went to see a chiropractor who was married to a musician friend, but after a couple of visits she said there was nothing she could do because the problem was not muscular but something else, perhaps neurological. She recommended another diagnosis and after tests it was discovered that Bill had a large tumor on his spinal cord. Fortunately it was benign, but it was impinging on his respiratory system so it would have to be removed or he would die. The surgery saved his life but left him all but paralyzed. He spent a gruesome nine weeks in hospital recovering and doing rehab to slowly walk again, later followed by grueling rounds of physiotherapy. Gradually some feeling and mobility returned but his right side was severely compromised and has remained so. He had no feeling in his right hand and only two working fingers on it and walked with a pronounced limp using a cane. His days of making a living as a reed-doubler were over. It was a tragic blow to someone who had worked so hard and it would have spelled the end for lesser men. Bill no doubt had many dark nights of the soul during this bleak time, but he had a lot going for him still. For one thing, he’s a mentally tough, very practical guy with a piece of flint buried somewhere deep inside him.

Local 802 of the Musician’s Union went to bat for him; the Musician’s Emergency Relief Fund paid his rent for a few months. His mind was unaffected, he remained as mentally sharp as ever and his phenomenal memory and eye for detail remained intact. And he’d made a lot of deep and lasting friendships over the years in the jazz community, which he could now look to for support, people rallied around as we shall see. But above all, shortly after getting out of the hospital he met Judy Kahn, who he would eventually marry. She’s a professional musician herself – classical flute and piccolo – among many other accomplishments. I haven’t met Judy yet, but have exchanged emails with her and know her to be a very organized, practical and positive lady with a witty sense of humour. It says a lot about her character that their relationship blossomed when Bill was at his lowest. They’ve been married for 22 years now and Bill insists that much of what he’s accomplished since his illness has been the result of her encouragement and support.

Eventually Bill was able to resume teaching which gave him some income. And he was able to use his literary chops and former writing associations and Smithsonian connections to drum up some work as an editor, annotator and producer during this time. In 1995 he co-produced Big Band Renaissance: The Evolution of the Jazz Orchestra, a superb five-CD survey of large-ensemble jazz from 1941 to 1991. The musical selections are terrific but best of all are the extensive and insightful liner notes he wrote for the accompanying 88-page booklet, offering a kaleidoscopic overview of big band jazz without being a tome. It’s hard to imagine anyone more qualified for this project and he won the 1995 NAIRD Indie Award for Best Liner Notes. This led to commissions for similar work with record labels such as Verve, Columbia and Mosaic.

He was involved in the production of Miles Davis and Gil Evans: The Complete Columbia Studio Recordings, and the liner notes which he contributed a major portion of won the 1996 Grammy Award for Best Album Notes. As noted earlier, he became heavily involved in producing CD reissues (and some new releases as well), writing the liner notes for over 50 of them, also selecting and sequencing compilations.

He edited A Miles Davis Reader, an anthology of writings on the iconic trumpeter’s trail-blazing career, including an article by Bill. Published in 1997 by Smithsonian Institution Press, it is, along with Jack Chambers’ Milestones I and II, the finest book on Davis I’ve read. Recently Bill used the knowledge he acquired about Davis to create a course he teaches on his music at Manhattan School of Music. He shared the course outline and listening selections with me as he was developing them and if I lived in New York I’d take the course in a minute. Ditto his course on Ellington. I know a fair bit about both men but would learn reams more from Bill.

In the late-nineties Bill’s friend, the legendary jazz historian Dan Morgenstern, recommended him to be editor of The Oxford Companion To Jazz, both a massive tome and a massive undertaking. Bill was initially reluctant to take it on but eventually came around. It involved picking the subjects and the writers to cover them, 59 in all. I don’t have the book but Bill has told me that his friend Johnny Mandel best described the task of editing it: “It must have been like being the contractor for the Ellington band.” It was like herding cats, involving several years of cajoling various writers from all around the world with wildly differing senses of work ethic to try to meet deadlines with something approaching promptness, reminding them that nobody got paid until their article was submitted. It won the Jazz Journalists’ Association 2001 Award for Best Jazz Book.

All of this writing, editing, producing and annotating kept Bill busy after his illness as well as furnishing him with an income along with teaching. But he missed playing and gradually he turned back to the saxophone. The fine bassist Sean Smith started coming by with his bass to jam, prodding Bill to play and encouraging him despite the rusty chops. If there was a small silver lining to his disability, it was that he eventually could still play the soprano, which had become his favourite, his ‘jazz horn’ of choice. The others were too big or small to manipulate or involved the wrong angles but the soprano was feasible, with some limitations. His compromised right hand was a problem, but eventually a brilliant saxophone repairman named Perry Ritter made some modifications to the keys of his soprano that helped overcome this. He still can’t play all of the notes on the horn so playing some written parts is an issue, but if he can pick his spots and choose what he’s going to play, Bill still has a beautiful and expressive jazz voice on the soprano. Of course it helps that he has a lovely tone, great ears and an improvisational insight governed by his composer’s mind. And as his old friend and teacher Lee Konitz counselled, “You can always simplify.” So, through great determination and a unique ability to turn limitations into advantages, Bill has been able to return as a vital jazz player. Of the nine albums he has released as a leader, four of them have come since 2001, well after his illness.

***

Returning to Bill’s first email to me in August of 2014, he surprisingly seemed to know I had a birthday coming up and asked for my address so he could send me a couple of his CDs as a gift, which would be a first step in remedying my unfamiliarity with his music. They arrived about a week later – Some Enchanted Evening from 1986, and Everything I Love, from 2004 – released in 2005. I forget why, but I listened to Evening first. It consists of eleven duo performances by Bill and three of his favourite pianists – Marc Copland, Mike Abene, and Harold Danko – recorded on a single day, September 30, 1986. The songs range from old standards such as the title track, “Bye Bye Baby”, “Alone Together” and others, to originals by Billy Strayhorn, Bill Evans, Miles Davis and two by Bill – “Silver Oaks” and “I Almost Said Goodbye”.

The opening track is a long exploration of the almost over-recorded chestnut “Autumn Leaves”, which has never sounded like this. It had me right from the start with Bill’s lovely and arresting abstraction of the familiar melody on soprano. Much like Lee Konitz would, he encapsulates and outlines its essence with a few essential notes which capture one’s attention immediately and set the tone for what will follow: a gentle but intensely ruminative probing of the old song. He and Copland are in almost telepathic sync throughout. There’s no explicit pulse yet it isn’t rubato either, there’s a loose but definite feeling of tempo which ebbs and flows. Without crowding or shadowing Bill at all, Copland seems to anticipate his every harmonic move as they peel away layers of the tune. At times it’s quite dense and at others more sparse and abstract but they stay in touch with the feeling of the song at all times. Eventually Bill stops and there’s an extraordinary shift by Copland as he plays alone, turning away from the song and then back to it. Eventually Bill returns and they take it “out”, in more ways than one. The track lasts for nearly 12 minutes, which shocked me because so much happened and yet it didn’t feel long because its spell seemed to stop time. It has become one of my favourite duo performances and probably my favourite version of “Autumn Leaves”. It’s an extraordinary introduction to Bill’s music and I was wrung out afterwards, pausing before moving on to the rest of the record.

One of the fascinating things about this record is the contrast between the three pianists and their interplay with Bill. It’s not just that each of them plays differently – that is to be expected – but that they actually make the same piano sound so different simply by how they strike it. I’m not going to parse the entire album – “Autumn Leaves” is the strongest track, but there are plenty of other outstanding moments on it and it requires – and repays – repeated listening. Another highlight is a daring take on “I’m All Smiles”, a dauntingly labyrinthine song to improvise on. Bill hit on the ingenious solution of eliminating the extended tag from the blowing choruses, which simplifies the structure considerably. With typical good grace and humour, Bill revealed that the song’s composer, Mickey Leonard, wasn’t too crazy about this alteration, but it’s the best jazz version of the song I’ve heard. “Bye Bye Baby” is another highlight, revealing Bill’s swinging and playful side.

Throughout, one notices his beautiful soprano sound – reminiscent of Steve Lacy, yet highly personal – and his wonderfully flexible phrasing and graceful sense of rhythmic shape and line. And above all, his commitment to compositional improvising; there are no licks or clichés here. I’ve mentioned Konitz and Lacy as players Bill reminds me of, and would like to add one more, which may strike some as a bizarre stretch: Pee Wee Russell. Seemingly Pee Wee and Bill are worlds apart stylistically and I’m not trying to suggest that Russell was a conscious influence. It’s just a personal observation meant as a compliment, but there’s something about the diffidently abstract way Bill sidles up to a tune, the way he uses his sound and pitch to make highly personal and obliquely subtle statements without using a lot of notes that strongly reminds me of Pee Wee.

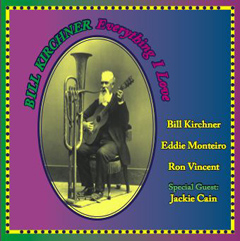

I needed, and took, a couple of days to digest Enchanted before moving on to Everything I Love, an entirely different animal altogether, recorded in 2004 well after Bill’s disability and featuring a delightfully bizarre cover photograph, taken from a postcard he received from a friend.

Bill’s liner notes opine it may be one of the most eclectic jazz albums released that year, but actually it’s one of the most eclectic jazz albums one could ever hear, period. It offers an extraordinary spectrum of moods, styles, sounds, tempos and repertoire delivered by just a trio of Bill on soprano, Eddie Monteiro on accordion and Ron Vincent on drums. I know what you’re thinking, folks – accordion – really!? But it’s Eddie Monteiro, probably the greatest jazz accordionist of all time. He runs the squeeze-box through a MIDI system, producing an astounding range of sounds suggesting organ, Fender Rhodes, strings, guitar, all with a wonderfully full bottom end worthy of a double bass – and remember I say that as a bassist. Plus he has a sense of harmony and voice-leading comparable to Bill Evans.

Beyond Bill’s ingeniously varied programming of tunes – the title standard, some attractive and interesting originals by Bill and others, a blues, a freely improvised workout entitled “Threedom”, a contrafact of “Body and Soul”, among others – Monteiro is a big reason this small group delivers such a big and varied sound. Ron Vincent, long one of Bill’s favourite drummers and a tower of sensitivity and power, is another. And for good measure, Jackie Cain (1928-2014), a good friend of Bill’s for about a decade, is on board as a guest singing two original Kirchner ballads: “Try To Understand” and “I Almost Said Goodbye”. Jackie was just short of 76 at the time of this date, her last appearance on record. Both songs are challenging to sing, wide-ranging and with some big interval leaps. She was one of the greatest ballad singers of all time and succeeds beautifully here, the purity of her voice and pitch moving me to tears. But the most arresting outing here belongs to Bill, on “For Steve Lacy”, an homage to the soprano saxophonist he admires the most. It’s Bill all the way, overdubbing his soprano on four tracks. It sounds, and is, freely improvised, and is perhaps the most “out” thing he has recorded, yet hangs together as a fully modulated sound collage, an abstract composition in the truest sense. Quite extraordinary.

I’ll return with further examinations of Bill’s music and records in Part Two of this piece, but for now would like to turn back to the man himself and the effect that knowing him has had on me. After all the effort he put into recovering from the tumor-removal surgery in 1993, his health failed him yet again in 2007. This is insupportable, to say the least, as Bill has basically been a jazz Boy Scout – never smoked or took drugs, always ate carefully, didn’t drink much – so why him? He was told the tumor had returned and, as another surgery was risky, radiation was recommended. He went for 30 treatments, which had disastrously unexpected results. The radiation shrunk the tumor but fried the myelin sheaths around his spinal cord, resulting in a further reduction in mobility and a sharp increase in his already chronic pain. He can still play but has reduced energy to do so, the few gigs he does are his own and carefully selected. He’s on a heavy regimen of pain-killers which haven’t dulled his mind one whit, but his mobility is decreasing slowly.

When I first met Bill in person in the spring of 2015 he could still get around using a cane on outings that involved the subway, albeit slowly and with great effort. He would use his electric scooter for neighbourhood outings but now uses it whenever he leaves his apartment. With typical practicality he’s become an expert on which subway stations have elevators and even has an app on his phone that updates him on which ones are out of service. His attitude in the face of this grimness is typically stoical and laced with gallows humour. Mostly he keeps on keepin’ on.

***

“Bill Kirchner is one of those rare musicians who is able to synthesize an awareness of the past with his own voice, taking jazz in new directions that are firmly based on tradition.” – Benny Carter

The above quotation leads off Bill’s website and is the most insightful single sentence about him I’ve come across, it says it all. It’s fitting – and a great honour – that it comes from Benny Carter, who is one of Bill’s all-time jazz idols, which is also apt as the two share a similar versatility as multi-instrumentalists and composer/arrangers, not to mention that they both personify classiness. Bill’s outlook and music have always been contemporary, yet his scholarly knowledge of jazz history also informs much of his work. He reveres the jazz tradition but also has time for those who go against its grain. His tastes are truly catholic, though he refers to himself as a “recovering Catholic.” As I’ve found out from our frequent exchanges which often trade YouTube clips, he’s as apt to send one of Dickie Wells with Django Reinhardt as he is one of Ornette Coleman or the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra on tour somewhere in Europe.

As a composer/arranger he loves big bands and appreciates musical precision and “good chops”, but also loves the risk-taking nature of freewheeling improvisation in a small band, or even a solo performance for that matter. Getting to know him has not only been a pleasure, it’s been like going to a jazz finishing school with no tuition. He’s introduced me to the work of important musicians I had never heard of before, such as Mike Crotty, Marc Copland and too many others to mention. And he has also made me more aware of musicians I knew of but perhaps didn’t appreciate or listen to enough, like Gregory Herbert, Mike Abene, Harold Danko, Steve Lacy, and many others. Without trying or any inculcation, he’s changed my mind about certain things. I now like the soprano saxophone a lot more than I did before and have a greater appreciation for the organization and finish good arranging can bring to a jazz performance, even one by a small group.

The biggest effect of all this has been to drag me out of the past a bit, if not altogether. I feel as though I was asleep for a lot of what happened in jazz from the ’70s on – actually it’s just that I was very busy mostly playing with guys much older than me – and Bill has woken me up and turned me on to some of the things I missed. I’m now in danger of being – dare I say it? – almost contemporary. All the food for thought he has provided me with has slowed down my writing quite a bit, which was not his intention, nor do I blame him. It’s just that I tend to think more before I write now, whereas before I’d just let her rip. So thanks, Bill, and get out of my head, would ya?

Without a doubt, Bill Kirchner is the most hard-core jazz character I’ve met, and I’ve known a few. Applied to him, the term “hard-core” might be a bit misleading as it has some unfortunate connotations with porn and bikers, as well as suggesting a personality that is perhaps intensely edgy, aggressive or loudly opinionated, maybe a bit pushy or extreme or narrow-minded. Bill is none of those; he’s soft-spoken, low-key, slightly built and mild-mannered, but with a wickedly dry and slightly wacky sense of humour. He does have a kind of low-fi chutzpah which has allowed him to talk his way into all sorts of situations, but this shouldn’t be confused with pushiness as he’s as apt to advocate for somebody else as much as for himself. Although he knows his own worth, he’s very modest and holds no extreme opinions, except perhaps on the medical profession. But misleading as it may be to call him hard-core, his intense commitment to jazz on so many fronts and his untiring doggedness in overcoming the ‘slings and arrows’ of such outrageous fortune leave me little choice. He’s a hard-core jazz survivor, a ‘lifer’ who has furthered the music in ways beyond counting.

***

(The first two photographs of Bill in this piece, both with his soprano, were taken by his good friend Ed Berger, a very accomplished jazz writer, photographer, record producer, and discographer who also served as Curator and eventually Assistant Director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University. Ed is one of the many jazz people Bill introduced me to in cyberspace and we had some pleasant exchanges from which I learned some interesting jazz tit-bits. He passed away on January 17, 2017 and is much missed.)

I‘ll return with Part Two shortly, mostly an account of my two visits with Bill in New York, some of our conversations and more about his music. In the meantime, here is a link to an excellent article on Bill Kirchner by Todd Bryant Weeks which appears in the April issue of Allegro, the monthly newsletter of Local 802 of the Musician’s Union of Greater New York City:

© 2018, Steve Wallace. All rights reserved.

Nice…

I met Bill in 2006 and have been his friend and student ever since. He introduced me to great music I hadn’t known existed (Rod Levitt is only one example) and to facets I never imagined of familiar musicians–who knew Pee Wee Russell recorded an album with Oliver Nelson?

When the subject is jazz history the only difference between Bill and Google is that Bill is a little faster and has a better sense of humor. We have other interests in common as well and his knowledge is as broad and deep in those, too. Great article, Steve.

And so my education continues. I remember Bill’s name but had no knowledge of his life, musicianship and experiences. Very interesting and informative article Steve.

I’m sure the article on Bill Kirchner (part 1) will stand as one of the best ever written about anybody. And by illuminating him you have illuminated all great Jazz Musicians. Terry

This portrait of Bill Kirchner is a great illustration of the kind of almost martyr-like dedication that jazz can bring out of people…that even health problems that would stop “lesser” artists is just a prod for those who are really taken over by jazz.

Can’t play any more? Write it! Can’t write it? Write about it! Teach it! Live it! The grit and stubborness of the true artist always shines through, and Bill Kirchner is the proof of that. Dizzy Gillespie was once asked if jazz was ‘serious music’. He said “People have died for jazz. THAT’S serious.” It’s just as serious that Bill has lived for it…

This might be the lengthiest of your posts, Steve, but I’m looking forward to Part 2!

I’m proud to say I’ve been a friend of Bill’s some 40 years but I’m a little surprised that you edited your post down to only two parts. He does so many things so well that if he ever takes up photography, I’m coming after him with a tripod.

…I’m assuming you’re a photographer, Mitchell!

Ain’t it a bitch when your good friends, professional at one thing, are better than you at YOUR profession? I’ve never considered myself a writer per se (though I’ve had to do a lot of it) and when someone like our host here, Steve Wallace, decides to “jot down” a few things I feel like tossing my old Smith Corona at him…

did you ever think of throwing your luggage at Steve

Mitchell Seidel is an excellent New Jersey-based photographer whose photos have graced many jazz recordings (including several of mine), jazz publications, and jazz clubs. He was formerly the photo editor of the New Jersey (Newark) Star-Ledger.

My deepest thanks to Steve for a truly staggering effort. Reading this piece has been like reading one of Whitney Balliett’s best New Yorker profiles–which says much more about Steve and his ability than it does about me. ‘Nuff said.

One again, Steve, you have done fine work. Very interesting and educational!