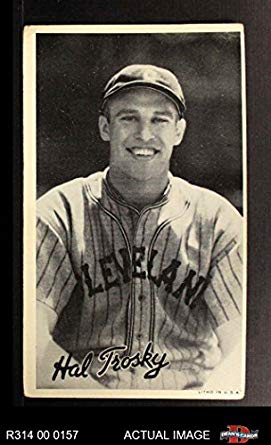

The words to Dave Frishberg’s great baseball song Van Lingle Mungo are all old ballplayers’ names and the name Hal Trosky appears at the end of the third system, which repeats later in the song. Trosky is now shrouded in obscurity, so a mention in such a hip, insider song is what passes for his moment in the sun these days. It has maybe kept his name alive somewhat and may have led a few jazz/baseball fans – hi, folks – to look him up, if only to answer the question: who the hell was Hal Trosky?

Well, he was a really good first baseman who played mostly for the Cleveland Indians, the bulk of his career occurring 1934-41. His career stats clearly show a very productive, powerful hitter whose typical season looked like this: a .302 batting average with 40 doubles, 27 home runs, 122 RBI and 100 runs scored. In 1936, he led the American League with a whopping 162 RBI and 405 total bases. Those are fantastic numbers, so why the obscurity? Well, context is everything and basically, he couldn’t win for losing. Get this – he played first base at the same time and in the same league as Lou Gehrig (still universally considered the #1 first baseman ever), Jimmie Foxx (#2 until Albert Pujols came along), and Hank Greenberg (a gigantic superstar 1934-40 and somewhere in the top 10.) I doubt if any player in history ever faced so much stiff competition at his position during his time. Despite being terrific, Trosky wasn’t just a second banana, he was a fourth banana.

The other thing is that he played for the Indians, who were pretty good then but didn’t win anything because almost all the AL pennants 1930-40 were won by Foxx’s A’s, Gehrig’s Yankees, or Greenberg’s Tigers. The only exception was 1933 when the Washington Senators somehow won a surprise pennant, but that was in Trosky’s rookie season when he only played a handful of games. Otherwise those other teams didn’t leave much meat, or glory, on the bone.

He faced some other adversity which didn’t help. His career was fairly short because in 1939, at 26, he began suffering severe migraine headaches which would incapacitate him for three or four days at a stretch. They grew worse and more frequent, sapping his power and causing him to miss significant playing time in 1941 and all of the 1942 and ’43 seasons – I always thought he was off fighting in the War. He tried to make a comeback with the White Sox in 1944 and again in ’46 but the headaches persisted, and he was done at 33. If not for the migraines, there’s no telling what Trosky might have achieved, but there’s no question that his performance from 1934 to 1938 was right up there with the very best.

Worst of all, Trosky’s legacy is unjustly tarnished by the exaggeration of his role in what became known as the “Crybaby Mutiny” of 1940. The Indians, managed by Ossie Vitt in his third season at the helm, were a great team that year with high hopes of winning the pennant. But Vitt, perhaps feeling insecure because of the high expectations, began throwing his weight around in spring training, suddenly revealing a personality and tactics that were a cross between Captains Bligh and Queeg, with a little Torquemada thrown in. He’d been a teammate of Ty Cobb’s back in the teens and like Cobb, he was polarizing, acerbic, creatively negative and perversely alienating.

In short, Vitt was a classic martinet and about as much fun in 1940 as a wolverine with a screwdriver stuck up its ass. For example, by May he had this to say about the young Bob Feller, easily the best pitcher in baseball that year: “Look at him. He’s supposed to be my ace. How am I supposed to win a pennant with pitching like that?” All Feller did that year was win 27 games with a league-leading 2.61 ERA and 31 complete games – what a bum. Vitt was also constantly critical of Mel Harder, a pitcher who had won 156 games in a Cleveland uniform up to that point and was as well-regarded as Feller. Early in the season, Vitt asked the press, “When is he going to start earning his salary?” Harder was a ten-year veteran and his salary that year was $12,000, relatively modest even in those days. Any of the other managers in baseball would gladly have taken either pitcher in a heartbeat, but they weren’t good enough for Ossie Vitt. No, sir.

As morale inevitably worsened, some of the players – seasoned, respected veterans, not kids – began to grumble that Vitt’s constant maniacal backbiting was keeping them from winning the pennant and wanted to demand he be fired. Trosky had been voted team captain and when he heard this talk he advised them to simmer down and not do anything rash. But as tensions mounted by the end of June, he finally agreed and joined several other veterans who went to team owner Alva Bradley and begged him to fire Vitt, backing up their position with a petition signed by most of the team.

Well……… it was 1940, not 1980, so you can imagine how this was received. Bradley flatly refused and The Cleveland Plain Dealer (yeah, right) got hold of the story and had a field day with it. The players were dubbed the “Cleveland Crybabies” and roundly vilified by the press and fans as a bunch of sissy, complaining country-club malcontents with no guts. Fans of the arch-rival Tigers delighted in calling them a “bawl team” and “half-Vitts”. Not surprisingly, whatever was left of team morale and unity went down the toilet but the players still put up a battle the rest of the season, finishing one game behind the pennant-winning Tigers. Ossie Vitt was fired at the end of the season and would never be given the reins of a major-league baseball team again. Amen.

Because he was the team captain, Trosky was portrayed as the ringleader and chief rabble-rouser in this revolt even though he’d initially tried to be the voice of reason. It dogged him for the rest of his career and I find it ironic that a guy with such an undeserved reputation as a labour agitator should have a last name just one ‘t’ short of Trotsky. You know, just in case the target on his back wasn’t big enough. Even more ironic, if that word will suffice, is that just after this baseball Potemkin went down, Trotsky himself was offed in Mexico with an ice-pick to the head by a Stalinist assassin in August, 1940. The way things went for Hal Trosky in Cleveland, it was lucky he didn’t meet with a similar fate. As it was, the horrible migraines he continued to suffer must have made the poor man feel as though he’d been stabbed in the head with a sharp object.

Truth is often stranger than fiction, provided your mind is strange enough to see it….

As a reward for hanging in with me, here’s Dave Frishberg’s Van Lingle Mungo:

© 2019, Steve Wallace. All rights reserved.

question–name the only non baseball player in the song —

Hi Ron,

When I first met Dave Frishberg in the early ’80s I told him how much I loved his song Van Lingle Mungo and he said thanks but that it had a mistake in the original lyrics – one of the names was not that of a player, but an umpire. As I recall, it was Art Passarella, who later went on to become an actor. But I think Frishberg corrected the mistake before recording the song. Is that right?

You’re correct about Art. You are really a baseball guy, Steve.

steve -you are correct–my earley versions still have in the song -a good article -rw

Does this come with Cliff Notes?

No Mitch, but I have some Cliff Jackson records lying around……….

Neat blog, Steve. I saw Dave at the Newport [Oregon] Jazz Party several years ago and he was great and have the tune on CD>. Have you heard about his health issues? Peter

steve! great tune. thanks.

here is the bluegrass version (or same idea) by John Hartford. Mentions a bluegrass bassist that plays jazz too.

https://youtu.be/8cbMQNl_OgE

Enjoy!

-tim posgate

Fantastic, Steve. I really love the game so much, even the way it is evolving these days…don’t get me started. (Did someone mention free agency?) And have always totally dug the Frishberg tune. My favourite moment in your essay: “suddenly revealing a personality and tactics that were a cross between Captains Bligh and Queeg, with a little Torquemada thrown in.”.

Paul

fine piece and wonderful song–the unknown language of baseball